Composers tend to steer clear of sprawling nineteenth-century tomes, with

their vast casts of characters and complex engagement with contemporary

social concerns. As far as I know, no-one has yet been brave, or foolhardy,

enough to turn Vanity Fair or À la recherche du temps perdu into an opera, although Prokofiev

didn’t let the 1500 page-count of War and Peace put him off.

Moreover, Jake Heggie’s 2011 opera Moby Dick used computer

graphics and elaborate staging to condense Melville’s mighty novel into a

streamlined form, while just this spring Charlottesville Opera presented a

chamber opera adaptation of Middlemarch by composer Allen Shearer

and librettist Claudia Stevens, which George Eliot scholar Delia Da Sousa

Correa described as ‘a concentrated expression of more of George Eliot’s

novel than one might think possible in a brief, two-act opera’.

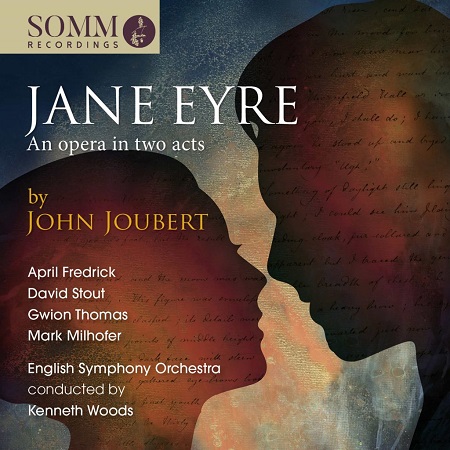

Composer John Joubert, who celebrated his 90th birthday this

spring, is best known for Christmas carols such as ‘Torches’ (1951) and

‘There is no rose of such virtue’ (1954) which have become staples of the

festival season. But, Joubert’s oeuvre is in fact extensive and

wide-ranging, comprising over 180 opus numbers: from operas - including

adaptations of George Eliot’s Silas Marner and Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes - to orchestral works, concertos, chamber

music, instrumental works, and both small- and large-scale choral pieces.

The South Africa-born, UK-domiciled composer has - according to David

Wordsworth’s account of Joubert’s achievements in the March/April issue ofChoir & Organ magazine, which is reproduced on the composer’s website - long found literature a

stimulus to his musical creativity: ‘The long and varied list of writers he

has drawn on (some notoriously hard to set to music) includes Emily Brontë,

Donne, Lawrence, Shakespeare, Yeats, Hopkins, Hardy, Rossetti, Mandelstam,

Ruth Dallas, Chesterton, and Crashaw, as well as Psalm settings and

numerous medieval texts.’

For ten years of his 70-year composing career, Joubert worked on an opera

adapted from Charlotte Brontë’s Gothic romance, Jane Eyre. An

adapted version was mounted by Opera Mint in 2005 but it was not until

October 2016 that the opera - which Joubert had revised further into a

two-act structure - received its official ‘world premiere’ at the Ruddock

Performing Arts Centre in Birmingham. That concert performance, by the

English Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Kenneth Woods, was recorded

and released by

SOMM

in January this year.

Librettist Kenneth Birkin has focused on Jane’s adult life, which deprives

us of the first stages, at Gateshead and Lowood, of Jane’s progress through

Brontë’s Bildungsroman but which sensibly makes Jane’s romantic trials with

Rochester and St John Rivers the central concern. Each act is divided into

three scenes. Act 1 begins on the eve of Jane’s departure from Lowood and

journey to Thornfield, where she takes up her position of governess. Scenes

two and three juxtapose Bertha Mason’s attempt to murder Rochester by

setting his bed alight, with a garden scene in which Rochester and Jane

declare their love for each other. Act 2 begins with the disruption of

their wedding ceremony by Bertha’s brother, before the action shifts

forward one year and presents Jane in the parlour of the Rivers’ cottage at

Whitecross where she has been given refuge. When St John attempts to

persuade Jane to join him, as his wife, as he departs for missionary work

in India, she desists and, haunted by Rochester’s anguished cries, ‘Jane!

Jane! Jane!’, returns to Thornfield where the final scene sees her reunited

with the now blind Rochester, who is at last free to marry her.

We learn less about the physical and emotional abuse that Jane experiences

at the hands of the Reed family, Mr Brocklehurst and Blanche Ingram, and we

lose some of Brontë’s cast of characters, including Jane’s childhood

friend, Helen, and the secretive, sinister Grace Poole. But, though the red

room episode would surely have made for a terrific set-piece, there are

several other scenes and passages which provide vivid theatre, including

the instrumental interlude which evokes Bertha’s midnight progress towards

Rochester’s bed and the interruption of Jane’s wedding by Bertha’s brother

before a morally outraged congregation.

Indeed, the latter scene breaks the opera’s prevailing pattern of duets and

short monologues. The scene begins with orchestral bustle, the brass and

timpani suggesting preparations for a public nuptial ceremony as well as

sounding a more ambiguous and ominous note. The declamatory lines in this

scene are Britten-esque: they brought to mind the trial scene at the start

of Peter Grimes, when Swallow summons Grimes into the dock, and

the censorious condemnations of the massed voices - ‘Bigamy!’, ‘It’s little

short of sacrilege!’, ‘In God’s house too’ - are no so far from the

Borough’s hypocritical denunciation of Grimes.

However, so much of the power of the novel depends on the strong

first-person narrative, through which the reader seems almost to connect

with Jane’s inner consciousness. As Jane, April Fredrick sings the opera’s

first words, joins with Rochester in a transcendent union at the close, and

is pretty much a constant participant in the action. And, both Fredrick’s

gleaming, focused soprano - which soars through Joubert’s lyrical lines -

and her vocal stamina are admirable.

The opening scene reminds me of the Governess’s first utterances in

Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, for the sweetness of Fredrick’s

sound suggests Jane’s eagerness and lack of worldly experience, though as

her soprano swells powerfully, the strength of Jane’s inner spirit is also

conveyed. As the opera unfolds, Fredrick’s communicates the full range of

Jane’s rapidly changing and diverse emotions. She is not intimidated by

Brocklehurst when he insists that she remain at Lowood, resisting his

overbearing menace as intimated by the orchestral surges and stabs, and by

the dark tone colours of low brass, strings and timpani. During her early

exchanges with Rochester, one senses Fredrick’s voice growing in focus and

presence as Jane matures and becomes conscious of her burgeoning love.

The garden meeting in which they voice their true feelings is tender, the

static harmonies and woodwind murmurings evoking both the tranquillity and

expectancy of the summer evening. Later in the scene, the more sensuous

colours and harmonies, the lilting rhythms and the horn’s mellifluousness

imbue their overlapping lines - ‘lay your head upon my breast’ - with

quasi-erotic emotion, which strengthens further as the two voices come

together in wonder, ‘Is it a waking dream?’ Jane’s duets with St John

Rivers are no less captivating: Fredrick is eloquent in resisting his

domineering insistence that she must join him in India, and when Jane hears

Rochester’s distant voice, calling her name, she finds the strength to

retain her integrity as the horn sings a gentle reminiscence of their

former love.

The characterisation of the entire cast is strong and communicative. David

Stout’s firm baritone suggests Rochester’s masculine confidence and

authority, though shades of darkness intimate inner troubles which

sometimes find expression in outbursts of Claggart-like self-pity and

frustration: ‘Fate has brought me home’, he despairs when reflecting on the

‘demon from pit of hell itself’ which separates him from his beloved Jane.

But, the snarling rasp, ‘hell’s gate’, is quelled by images of Jane’s

‘sweetness - innocence’, and Stout’s voice softens tenderly. Later, blinded

by the Thornfield fire and alone in the overgrown garden, Stout shapes his

low utterances to suggest Rochester’s sad resignation and exhaustion,

though as he recounts the tale of Thornfield’s destruction his baritone

burns with yearning - ‘Jane, where are you now? I miss you so.’ - and then

angry misery: ‘Am I forgotten then?’ The joyful warmth of the impassioned

reunion scene leads to a transcendent closing duet.

Gwion Thomas’s Brocklehurst is imperious and domineering, his enunciation

crisp and commanding; one can easily picture a nineteenth-century autocrat

accustomed to seeing women and children cower in response to his bullying

decrees. St John Rivers is sung by Mark Milhofer, whose penetrating tenor

suggests a man driven by missionary zeal and contrasts strikingly with the

delicate adorations of his sisters Diana and Mary. The diction is uniformly

excellent and the singers are never overwhelmed by the orchestral fabric,

the textures of which are lucid, allowing the many evocative instrumental

details to be remarked.

A forty-page booklet contains both synopsis and complete libretto, as well

as essays by Joubert, Kenneth Woods and Christopher Morley; the latter’s

interview with Joubert is included at the end of CD2 and provides an

intriguing supplement. The recording is bright and clear, and there are no

‘intrusions’ from the live audience.

Joubert has remarked, ‘The criterion I use for the selection of operatic

subjects is that they should comment in some way on basic human issues,

thus bringing them into line with the Enlightenment idea of theatre as a

‘School of Morals’’. Indeed, some might argue that Brontë’s novel verges on

the didactic, with the characters experiencing a series of ethical crises

in a world where morality and romantic love seem to be mutually exclusive.

However, at the close, though it’s perhaps not clear whether Jane’s

decision to return to Rochester is driven by her morals or her emotions,

the final scene of Joubert’s opera sees the beloveds’ souls ‘joined as one

… before God’s throne’. But, if there is peace and reconciliation at the

close, then Joubert’s opera certainly makes tangible what Virginia Woolf

described as Jane’s very modern sense of ‘self’, as she ‘resist[s] all the

way’. In so doing, Joubert’s Jane Eyre communicates much about the

particularities of individual human experience.

Claire Seymour

John Joubert (b.1927): Jane Eyre - opera in two Acts Op.134

Jane Eyre - April Fredrick, Edward Rochester - David Stout, Mrs

Fairfax/Hannah - Clare McCaldin, Revd. St John Rivers/Richard Mason - Mark

Milhofer, Mr Brocklehurst - Gwion Thomas, Sarah/Diana Rivers - Lesley-Jane

Rogers, Leah/,Mary Rivers - Lorraine Payne, Rector’s Clerk - Joseph Bolger,

Revd. Wood/John - Alan Fairs Samuel Oram - A servant, Verger - Andrew

Randall, Briggs - Andrew Mayor; Conductor - Kenneth Woods/English Symphony

Orchestra.

rec. live, 25 October 2016, Ruddock Arts Centre Birmingham (premiere)

SOMMCD263-2 [58:19 + 48:26/17.30 (Christopher Morley in interview with John

Joubert)]