Returning from the Trojan Wars, his ships and crew threatened by a tempest,

the Cretan King Idomeneo bargains with the sea-god Neptune in order to save

his own skin, and in so doing risks losing his son, by his own hand. Having

vowed to sacrifice the first person he meets upon his safe arrival on his

home shore, Idomeneo is greeted by his son, Idamante, and finds himself

conflicted by the demands of love and duty. Mozart’s opera seria

dramatizes the King’s attempt to unravel the mess of his own making, as

rivalries, jealousies and intrigues fester and flourish at his Cretan

court. As so often with the Greeks’ tragic tussles, the modern-day

parallels are painfully apparent.

However, in contrast to Austrian director Martin Kušej’s approach at

Covent Garden in 2014

, director James Conway has eschewed the idea of turning the opera into, in

his words, a ‘specific history lesson’, and the untrammelled simplicity of

his conception and its execution in this ETO production of Idomeneo begets rich results. This is a production characterised

by musical insight, dramatic composure and technical excellence, on the

part of the creative team and cast equally. In a programme article, Conway

confesses that he has previously hesitated to direct Idomeneo,

fearing its ‘relentless earnestness’, but here he makes such sincerity a

virtue: this Idomeneo is notable for its clarity, candour and

communicativeness.

Katie Mitchell’s modern-day for production for

English National Opera (2010) had assorted pen-pushers, waiters and flunkies dashing about the stage in

what I described at the time as an ‘unexplained and unfathomable flurry of

activity’. Conway’s approach could scarcely be more different. Here, music

and mise en scène work their magic, aided by Frankie Bradshaw’s

clear-cut designs and Rory Beaton’s bold lighting - how apt for an opera

whose hero is the epitome of Enlightenment values.

Catherine Carby (Idamante), ETO Chorus, Galina Averina (Ilia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Catherine Carby (Idamante), ETO Chorus, Galina Averina (Ilia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Beaton’s lighting schemes pit strong primary and complementary hues against

each other. Colours transmute - aquamarine and orange, purple and red -

sometimes with a swiftness matching the briskness with which many of

Mozart’s arias follow the recitative, elsewhere more organically. The

palette and brightness, by turns intensified and muted, evoke locale - the

infinite ocean, a waterfront, the stormy sky - and mirror inner passions.

The stage is quite foreshortened by an imposing edifice which stretches its

length, but a mosaic-bordered exit stage-right suggests a depth beyond -

what Conway describes as ‘a doorway leading to something suggesting

culture’ - and sliding panels concertina to open up vistas, revealing the

Cretan populace, who suffer as a result of their ruler’s failings, and the

captured Trojans who are confined in a prison evoked by a slanting panel

which tilts menacingly. The ETO Chorus, though distanced for much of the

production - placed ‘beyond’ the struggles within the court, but no less

affected by them - were in strong voice.

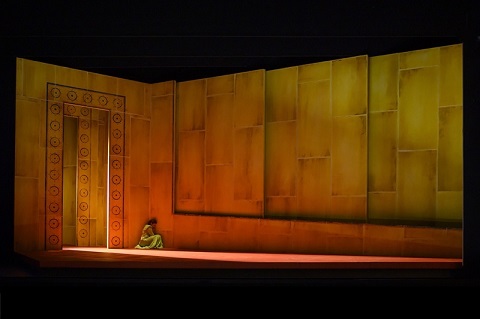

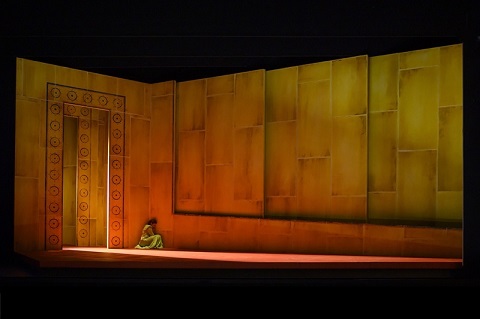

Christopher Turner (Idomeneo). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Christopher Turner (Idomeneo). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The cast, too, offered consistently fine Mozartian singing. As Idamante,

mezzo-soprano Catherine Carby made us feel each and every of the young

Prince’s emotional twists and turns. This Idamante wore his heart on his

tunic-ed sleeve and Carby acted and sang with candour, the richness of her

voice particularly expressive in the recitatives. On the last few occasions

that I’ve heard Christopher Turner perform (at SJSS in

La Nuova Musica’s Alcina

early this year, and as Pollione in Chelsea Opera Group’s

Norma in 2018) I’ve been more and more impressed by the combination of focus,

power and beauty that his tenor commands. He displayed plenty of ringing

heroism as Idomeneo, compelling our attention: the bravura of his Act 2

aria, ‘Fuor del mar’, conveyed both the King’s regal stature and his

self-inflicted anguish and fear. Turner has a strong lower range which

brought out the darkness within this morally questionable monarch; but

there was lyrical shapeliness too in Act 3’s beautifully shaped ‘Accogli, o

re del mar’.

Galina Averina (Ilia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Galina Averina (Ilia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

As Ilia - the daughter of the defeated King Priam of Troy who, rescued at

sea by Idamante, has fallen in love with the son of her enemy - Galina

Averina had the difficult task of establishing the mood at the start of

both halves of the performance, but she did so with consummate poise. Alone

on stage, she opened Act 1 as a figure of loneliness and loss, curled

against the wall as if trying to protect herself or escape from the

conflicts within the palace and within her own heart. Averina has a lovely

soft gleam to her sound, which was complemented by the woodwind quartet in

Act 2’s ‘Se il padre perdei’; and, while ‘Zeffiretti lusinghieri’ was

similarly moving, Averina was able to bring urgency to her tone when

required.

Paula Sides (Elettra). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Paula Sides (Elettra). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Paula Sides seemed a little hesitant initially as Elettra - the daughter of

Agamemnon and Clytemnestra who has taken refuge among the Cretans after her

brother Orestes has committed matricide, and who is Ilia’s rival for

Idamante’s love - but her Act 2 aria ‘Idol mio’ was rich with emotions

which exploded further in her final aria, ‘D’Oreste, d’Ajace ho in seno i

tormenti’. In the latter, the torments of Elettra’s own unrequited passion

and of her brother’s crime fused in a glittering fiery outburst. Sides

captured Elettra’s vengeful vindictiveness and her pathos; as she yearned

to follow Orestes to the abyss, the shapes carved by her soprano were as

sharply defined as the edge of the knife she wielded.

The roles of Arbace, the King’s counsellor, and the High Priest were

amalgamated and sung with vigour and urgency by John-Colyn Geantey, though

perhaps a bit less dashing about would have brought more gravity to the

High Priest’s persona. As the Voice of Neptune, Ed Hawkins was fittingly

resonant and imposing. The ETO Orchestra played with brio for conductor

Jonathan Peter Kenny who created fluency between the recitatives and arias,

which are often conjoined in the score.

Christopher Turner (Idomeneo) and John-Colyn Geantey (Arbace). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Christopher Turner (Idomeneo) and John-Colyn Geantey (Arbace). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Heading towards disaster, Idomeneo can only hope for divine intervention

and mercy. He and subjects are fortunate: it proves easier for the Cretan

King to do a deal with the deities than it evidently is for some modern-day

leaders to negotiate with their counterparts abroad and their ‘allies’ at

home. And so, Idomeneo’s reckless promise is revoked and order restored.

Idamante slays the sea monster and buries past conflicts, and while

Idomeneo has to relinquish power to the next generation, the continuity of

the family line is ensured, as a new world begins. If only we could be so

lucky.

The regicidal Macbeth, too, might wish for similar good fortune, for in

Shakespeare’s Scottish play supernatural interventions bring not

reconciliation and renewal but deceit and destruction. Not that the witches

in James Dacre’s production are particularly menacing, although the female

Chorus sang with vigour and precision. At the start, cloaked in green

habits and white aprons, this gaggle of nuns-cum-nurses tend to the wounded

and lay out the dead, all the while singing of the vicious torments which

they have inflicted upon the unfortunates who have crossed them. These are

not Shakespeare’s ‘withered and so wild’ hags with ‘choppy fingers’,

‘skinny lips’ and ‘beards’ who emerge from mist and dissolve into darkness;

nor the ‘compound’ figures in Verdi’s opera who - as shaped by the

composer’s interest in the writings of Shakespeare’s German translator

August Schlegel - are both emblems of the superstitious lower classes and

Delphic agents of fate. Instead, this ministering brood, medicinal rather

than murderous, might have looked more at home in a G&S operetta - or,

when Verdi’s rum-te-tum choruses are given a cheery boost by conductor

Gerry Cornelius, on the set of The Sound of Music. Thus, when

Macbeth and Banquo, fresh from their trouncing of the merciless Macdonald

and with the traitorous Thane of Cawdor’s limp body swinging from a noose

at the rear of Frankie Bradshaw’s twilight-zone set - meet the witches for

the first time, their query, ‘What are these foul beasts?’, falls rather

flat.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The representation of the witches seems to me to be central to the impact

that the opera makes, especially because of the identification with the

witches that Lady Macbeth’s music intimates. Christoph Clausen (in

Macbeth Multiplied: Negotiating Historical and Medial Difference

Between Shakespeare and Verdi) has argued that although a comic treatment of witches was the norm in

late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century theatre, by the mid-nineteenth

century witches were depicted on stage as more sinister figures. But, even

if Clausen is correct, we have Verdi’s directives to his librettist

Francesco Maria Piave, in letters written during September 1846, that he

should ‘adopt a sublime diction, except in the witches’ choruses, which

must be vulgar, yet bizarre and original [triviali, ma stravaganti ed originali]’. What did Verdi mean by

‘trivial’? Verdi scholar Julian Budden has claimed that the first witches’

chorus merely captures the ‘childish malice’ of the witches in

Shakespeare’s play, while the second ‘has all the deliberate vulgarity of

its predecessor without any of the fantasy. It is just any chorus of

gipsies or peasants.’ Whatever, representing the witches as sisters of

Christ doesn’t seem to me to make much sense: the witches inflict pain

rather than assuage it.

The opera is presented in English and this, too, seemed to me to be

misguided. Of course, exigencies of dramatic form and pace necessitated

excisions which alter relationships and motivations in the opera: thus,

Verdi’s Lady Macbeth becomes unequivocally a dominating demon rather than

just an instigator, encourager and accomplice, and she is the mastermind of

the plot to murder Banquo, rather than a caring wife pushed aside by her

increasingly isolated and sick husband. Also, Verdi was himself more

influenced by the various Italian translations of Shakespeare than directly

by the Bard’s text itself, although, in the face of criticisms of his

libretto, Verdi wrote to Léon Escudier, his French publisher (April 1865),

complaining that although he was accused of not ‘knowing his Shakespeare’,

‘in this they are very wrong. It may be said that I have not rendered Macbeth well, but that I don’t know, don’t understand, and don’t

feel Shakespeare-no, by God, no. He is a favourite poet of mine, whom I

have had in my hands from earliest youth, and whom I read and reread

constantly.’

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The point here, though, is that Andrew Porter’s translation is a prosaic

paraphrase of Shakespeare’s poetry which reduces the emotive impact of the

words. For example, Macbeth sees ‘gouts of blood’ upon the blade and

dudgeon of the hallucinated dagger: why change this to ‘drops of

blood’? End-of-scene summaries are also offered; but surely there can be

few in the audience who are unfamiliar with the basic plot. An Italian text

would have retained the lyricism and rendered an emotional heightening

of the tragedy.

What Dacre’s production does do successfully is to bring the political

rather than the personal to the fore: after all, premiered in Florence in

1847, at the height of unrest about Italian reunification, Macbeth surely articulates Verdi’s devotion to Italian

independence and his abhorrence of the tyrannical abuse of power.

Bradshaw’s set is a concrete bunker, which harbours secret niches and

nooks, permitting intrigue and, in the Grand scena and duet in Act 1,

intimacy. Infernal intrusion, too, when the ghost of Banquo - bloodstained

but not quite shaking ‘gory locks’ at the hysterical Macbeth - imposes

himself behind the throne positioned and raised in the central recess. CCTV

cameras capture the corruption, and attest to Macbeth’s paranoia; until,

that is, a black-clad assassin disables them prior to Banquo’s murder.

Dacre updates the drama to the modern age: Macbeth and Banquo swap their

officers’ regalia for sharp suits, while Lady Macbeth sports attire

suggesting executive power. As rag-bag mercenaries in combat fatigues,

beanies and balaclavas dash about the stage, the effect is pacy and punchy

- though I winced when Ruger MK I’s were waved menacing at the mention of

swords and daggers.

Madeleine Pierard (Lady Macbeth) and Grant Doyle (Macbeth). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Madeleine Pierard (Lady Macbeth) and Grant Doyle (Macbeth). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The singing, too, provides much enjoyment. As Lady Macbeth, Madeleine

Pierard may not comply with Verdi’s request for ugly, declamatory sounds

and hollow whispers, but she does make a good effort to use vocal colour to

portray complexity of character and the dangerous energies of Lady

Macbeth’s inner life. There’s a false note in the sleep-walking scene,

though, when Lady Macbeth puts out her own light, for the taper that she

carries - ‘she has light by her continually; ‘tis her command’, so her Gentlewoman

tells us - is her only defence against the darkness which she has summoned

and delighted in and which now consumes and terrorises her.

Macduff is reduced to a minor role by Piave and Verdi, but Amar Muchhala

makes his aria count, singing expressively and with dramatic impact. Andrew

Slater is vocally woolly-edged as Banquo but he establishes a nice rapport

with Dara Gibo’s Fleance, the latter’s suitably guileless and vulnerable

demeanour evoking a pathos which is rare in this production.

Andrew Slater (Banquo) and Dara Gibo (Fleance). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Andrew Slater (Banquo) and Dara Gibo (Fleance). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

ETO regular Grant Doyle rages and rampages as Macbeth but achieves volume

at the expense of subtlety of characterisation and nuance of vocal line.

This is a broad-stroke interpretation, and while Doyle has an appealing

baritone it feels pushed to the limit at times here; there is little sense

of the interior life - the conscience and guilt which make Macbeth a ‘man’

rather than just a murderous tyrant. Even his final aria, ‘Mal per me che

m’affidai’, though sung with intensity and focus, did not quite capture the

sense that this is a turning-point, a moment when Macbeth truly regrets his

actions recognising that they have brought him a ‘power’ which is transient

and false, and that he has denied himself the honour, love, obedience and

friendship which should accompany old age.

Cornelius keeps the action surging forward and, attentive of the details of

orchestration, conjures the dark tinta of the score.

English Touring Opera’s

2019 Spring Tour

continues until June 1st.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: Idomeneo

Ilia - Galina Averina, Idamante - Catherine Carby, Idomeneo - Christopher

Turner, Arbace - John-Colyn Gyeantey, Elettra - Paula Sides, The Voice of

Neptune - Ed Hawkins; Director - James Conway, Conductor - Jonathan Peter

Kenny, Designer - Frankie Bradshaw, Lighting Designer - Rory Beaton, ETO

Chorus and Orchestra.

Hackney Empire, London; Friday 8th March 2019.

Verdi: Macbeth

Macbeth - Grant Doyle, Lady Macbeth - Madeleine Pierard, Banquo - Andrew

Slater, Macduff - Amar Muchhala, Malcolm - David Lynn, Lady-in-Waiting -

Tanya Hurst, Doctor - Ed Hawkins; Director - James Dacre, Conductor -

Gerry Cornelius, Designer - Frankie Bradshaw, Lighting Designer - Rory

Beaton, ETO Chorus and Orchestra.

Hackney Empire, London; Saturday 9th March 2019.