Director Deborah Warner, whose production of Billy Budd (a

co-production with Madrid’s

Teatro Real

and Rome Opera) is the first for twenty years to grace the stage of the

Royal Opera House, seems to be in accord with the views that Benjamin

Britten expressed in a 1960 radio interview. For, it is Vere’s moral

dilemma which dominates her interpretation. She makes no attempt to, as

Britten’s librettist E.M. Forster put it in The Griffin in 1951,

‘tidy up Vere’: ‘We (Eric Crozier and I) have, you see, plumped for Billy

as a hero and for Claggart as naturally depraved, and we have ventured to

tidy up Vere’. In Warner’s production, Toby Spence’s Vere is undoubtedly

“lost on the infinite sea”.

Michael Levine’s quasi-abstract design and Jean Kalman’s atmospheric

lighting emphasise this. The sea is metaphoric. Forster had written to

Britten, with striking prescience, ‘I will not recall you to the sea. Much

as I love it, I believe that you ought to postpone it until you can create

an old-man’s sea. Anyhow much later in your career’.

[1]

Here, platforms rise and fall (presumably intermittently obstructing the

view of those seated in the upper ‘decks’ of the House) and the sea is

evoked only by a trough of water across the centre of the stage (again,

presumably not visible to patrons in the stalls) through which shipmen

stomp and splash, to little evident purpose - Alasdair Elliott’s Squeak

seems particularly partial to a paddle. Although there are nautical

emblems, and we climb up to the mizzen-top and down into the ship’s

underbelly, Levine and Warner make us imagine the expanse of ocean on which The Indomitable drifts and we sail instead through the mists and

tidal surges of a psychological seascape. As Britten’s designer, John

Piper, had urged, ‘We must never forget that the whole thing is taking

place in Vere’s mind, and is being recalled by him”.

[2]

The criss-cross of ropes, rigging and ladders that pattern the ROH stage

suggest not just the regimented discipline of naval life but the net which

entraps Vere, Claggart and Budd - even the Novice, who laments, “Oh, why

was I ever born? Why? It’s fate, it’s fate. I’ve no choice. Everything’s

fate.” And, Vere might plead, “O for the light, the clear light of Heaven”,

but Kalman’s hazy, grey hinterland offers no illumination. We are adrift.

The costumes, too, blur and confuse: if the design evokes a late

eighteenth-century frigate, then Chloé Obolensky’s naval uniforms refer to

the Second World War, and I’m not sure what is gained by simultaneously

intimating ‘modern’ times and post-Revolutionary France.

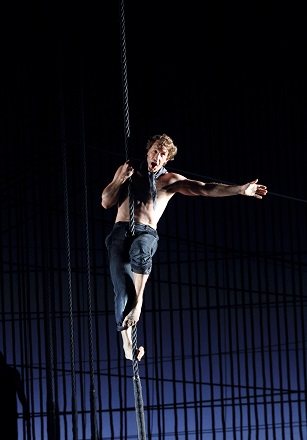

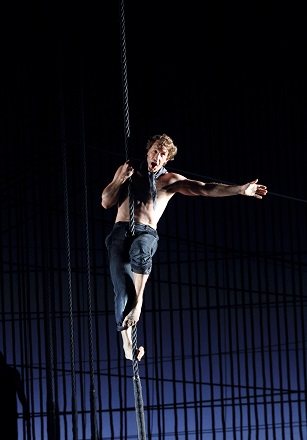

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Moreover, although Kim Brandstrup deftly choreographs the crew’s work and

leisure - the ROH Chorus, who sang with stirring passion, are supplemented

a thirty-strong group of actors - there is little sense of actual

‘movement’. In the opening moments, the sailors’ work-cry, “O heave! O

heave away”, sees them on their knees, scouring the deck with holystones

rather than tugging the ropes and rigging. They remain unmoved by Billy’s

rallying summons, “Sway!”, and there is no sense of the integrative force

that binds the men and which later erupts during the pursuit of the French

frigate - here, despite the surging violence in the score, an episode which

fails to evoke vigorous anticipation of victory - and after Billy’s

hanging, when the crew reprise his unintentionally seditious farewell to

his former ship, The Rights O’ Man, the ‘heave’ motif returning as

a mutinous, threatening undercurrent. Kalman’s lighting emphasises the

motionlessness, confining Vere to his cabin and the men to their hammocks

in the hull.

Toby Spence (Captain Vere), Thomas Oliemans (Mr Redburn) Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Toby Spence (Captain Vere), Thomas Oliemans (Mr Redburn) Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The homoerotic sub-currents of both Melville’s novella and Forster’s

libretto remain submerged in Warner’s production, and it is the opera’s

religious allegory which is brought to the fore. There’s no doubting the

answer to Vere’s desperate questions in the Prologue: “Who has blessed me?

Who has saved me?” Just as Warner, in interview, described Claggart as a

“fallen angel”, so this Billy is unambiguously seraph-like. Forster noted

(in The Griffin) that some critics had surmised that Billy’s

‘almost feminine beauty’ and ‘the absence of sexual convulsion at his

hanging’ indicate that Melville intended him as a ‘priest-like saviour’,

but while he professed to have striven to emphasise Billy’s masculinity and

‘adolescent roughness’, Forster couldn’t resist portraying Billy’s hanging

as a Christ-like sacrifice. And, Warner follows his lead, most strikingly

during the ‘hidden’ interview between Vere and Billy before the sentencing.

For, though Britten and Forster followed Melville - ‘Beyond the

communication of the sentence, what took place at this interview was never

known.’ - in this production the interview does not take place behind

locked doors. As the orchestral ‘interview chords’ unfold, Billy moves to

the rear of Vere’s private quarters; when he is sent down into the hold by

the conscience-wracked Vere, Billy places a palm on his Captain’s forehead

- an unequivocal gesture of compassion and clemency. But, while scholars

have essayed various affirmative interpretations of the chords’ exposition

of the opera’s essential conflicts, their ‘meaning’ inevitably remains

obscure, just as the secrets of the locked room surely must remain

undisclosed. The power of the chords is emotional, not rational. As Vere

himself says, “I must not too closely consider these mysteries. As

mysteries let them remain.”

Clive Bailey (Dansker), Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Clive Bailey (Dansker), Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Toby Spence may look rather too youthful to embody the “old man who has

experienced much” who presents himself before us in the Prologue - here an

‘aged’ double sat stage-left, scouring the deck, perhaps in an attempt to

erase past ‘sins’ - but he captured Vere’s dreamy self-absorption and lack

of self-knowledge, shaping phrases and text with care and insight. This

Vere retreats from the realities of life aboard a war-ship to read

philosophy in his bath-tub, hosts his officers in his cabin while attired

in his dressing-gown, and rolls up the carpet to lie down so that he can

enjoy the sound of his men singing in their hammocks below: “Where there is

happiness there cannot be harm,” he declares, evading his crew’s discontent

through self-delusion. Warner’s direction frequently pushed Spence to the

rear of the stage, and his light tenor did not always carry with sufficient

weight, though Britten’s scoring helped him in the more declamatory

outbursts.

Indeed, this ‘Starry Vere’ seemed remarkably remote from his men. It’s hard

to imagine that he would inspire loyalty and love of the intensity which

drives Billy to vow, “I’ll look after you my best. I’d die for you - so

would they all.” Introspection characterises Spence’s Vere; I was not

convinced that he was, as Forster and Melville emphasise, ever aware of his

duties as a ‘King’ aboard the Indomitable, the upholder of God’s

laws, charged with maintaining cohesion and stability. Such professional

responsibilities influence Vere’s actions during the trial scene, but

Warner emphasises instead the personal dimension: the three officers -

Flint (David Soar), Redburn (Thomas Oliemans) and Ratcliffe (Peter Kellner)

seem both shocked and disappointed by Vere’s refusal to save Billy, and

thus it is his personal anguish which is foregrounded, and separated from

the pressures and tensions of life on-board a ‘floating prison’.

Jacques Imbrailo’s Billy Budd has become well-known to us now, since he

first sung the role at

Glyndebourne

in 2010. Imbrailo, as always, performed with physical and vocal

muscularity, hauling himself up a rope with impressive strength to bid

goodbye to his former ship, effortlessly flooring Squeak in a vicious cabin

scuffle, lashing out impulsively at Claggart. If initially his baritone

lacked a little of the golden gleam that shines from Billy, then the slight

ruggedness of tone was put to excellent effect during Billy’s reflections

‘in the Darbies’; this was a beautifully modulated and deeply moving

expression of understanding, forgiveness and vision.

Brindley Sherratt (Claggart). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Brindley Sherratt (Claggart). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Brindley Sherratt’s portrait of Claggart was nuanced and chilling. His

Credo was a high-point: one could feel the forces struggling for control of

Claggart’s psyche. As Forster said, ‘Claggart gets no kick out of evil as

Iago did’, and Claggart tempered menace with melancholy, violence with

vulnerability. Claggart’s wretchedness - “O beauty, O handsomeness,

goodness! would that I had never seen you” - is deepened by the staging

which places the master-at-arms on an upper deck with the slumbering figure

of Billy huddled in a hammock below, illuminated by a shaft of light which

penetrates Claggart’s shield of darkness, exposing what Meville describes

as the master-at-arm’s ‘natural depravity’.

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The cast was uniformly strong. Duncan Rock’s Donald made a strong

impression; Clive Bayley was a surly old sea-dog but revealed Dansker’s

true heart in Billy’s time of need. Sam Furness made much of the Novice’s

role, working hard with the text and communicating the young lad’s

ignorance and innocence. Furness sang the Novice’s Dirge with honest

feeling, as, encouraged by his caring friend (Dominic Sedgwick), he dragged

himself the full length of the deck, unable to walk or stand after his

flogging. Thomas Oliemans’ Mr Redburn was an authoritative figure, matched

for vocal sureness by David Soar’s Mr Flint and Alan Ewing’s sonorous

Bosun.

Conducted by Ivor Bolton, the ROH Orchestra were powerful in the climactic

passages of Britten’s score, but there was occasional discrepancy between

stage and pit.

In the Epilogue, Vere torments himself with accusations and questions - “I

could have saved him. […] O what have I done?” - but takes comfort from

Billy’s absolution: “He has saved me, and blessed me, and the love that

passes understanding has come to me.” Britten’s music, though, is

characteristically more equivocal. Vere professes to have sighted the

“far-shining sail” and to have “seen where she’s bound for”, but the

strength of Warner’s production lies in its ability to show us that the

light from heaven for which Vere longs will not separate good from evil;

that as Vere acknowledges “the good has never been perfect”; that, though

Vere has gained self-knowledge, the certainly of salvation remains elusive.

Claire Seymour

Billy Budd - Jacques Imbrailo, Captain Vere - Toby Spence, John Claggart -

Brindley Sherratt, Mr Flint - David Soar, Mr Redburn - Thomas Oliemans,

Lieutenant Ratcliffe - Peter Kellner, Red Whiskers - Christopher Gillett,

Novice - Sam Furness, Squeak - Alasdair Elliott, Dansker - Clive Bayley,

Arthur Jones - Thomas Barnard, Bosun - Alan Ewing, First Mate - Ross

Ramgobin, Second Mate - Simon Wilding, Maintop - Konu Kim, Novice’s Friend

- Dominic Sedgwick; Director - Deborah Warner, Conductor - Ivor Bolton,

Designer -Michael Levine, Lighting Designer - Jean Kalman, Costume Designer

- Chloé Obolensky, Choreographer - Kim Brandstrup, Orchestra and Chorus of

the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 23rd April

2019.

[1]

Undated letter, E.M. Forster Collection, King’s College Archives,

University of Cambridge

[2]

In, ‘Billy Budd on the Stage: An Early Discussion between

Producer and Designer’, Tempo, Autumn (1951), 21.