In the beginning, then, was Orpheus, his myth repeated, elaborated upon,

throughout Western musical tradition, and especially throughout Western

operatic tradition. It is surely no coincidence that it was with this

monumental work that Birtwistle sought his most radical extension yet of

that line. He wanted, he said, ‘to invent [my italics] a formalism

which does not rely on tradition in the way that Punch and Judy,

my first opera, relied on tradition. There I used forms such as the

chorale, toccata and gavotte. I injected them into my work just as Berg

injected formal ideas into Wozzeck. In The Mask of Orpheus, I didn’t want to hark back any more; I wanted

to create a formal world that was utterly new.’

Expectations could not have been higher. For some, yours truly included,

this was a moment for which we had been waiting the whole of our musical

lives. From a career strewn with masterpieces, here came at last a second

staging of Birtwistle’s Mask of Orpheus: heard only once complete,

in concert, since its 1986 premiere, and never since seen in the theatre. I

had previously only managed to hear a

single act, in concert, at the Proms

: an unforgettable experience that only increased my hunger to hear - and

to see - more. Present at that first, ENO performance, Alfred Brendel

extolled The Mask of Orpheus as the first English musical

masterpiece since Purcell. Many will find that view a touch harsh on

some music

and composers - even assuming Handel’s exclusion - intervening. Be that as

it may, no one with any serious interest in music or opera, indeed no one

with a passing interest, yet possessed of half an ear and a little

curiosity, would deny the work’s stature.

Katie Stevenson, Charlotte Shaw, Katie Coventry. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Katie Stevenson, Charlotte Shaw, Katie Coventry. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Musical values were high, as they would have to be: there is no more point

putting on Birtwistle with musicians unequal to its challenges than there

is Stockhausen. That excellence we heard from ENO forces should

nevertheless not be taken for granted. The conflict between rational and

irrational, between what Orpheus must do to win back Eurydice and what his

urge to act as a human being, a conflict as old as that between Apollo and

Dionysus and in many respects to be identified therewith, lies at the heart

of this work. The climax to the second act, indeed the whole of that

extraordinary structure of recollective arches, not only retains its

enormous, truly post-Wagnerian power; it seems to increase with every

hearing. This proved no exception. One was truly left reeling then - and

not only then - at least insofar as one could separate the musical

performance from its sadly inadequate scenic realisation, on which more shortly.

Moreover, if that conflict between the demands of reason and those of

emotion lies at the work’s dramatic heart, so too does the variety of ways

in which its participants, us included, might look at, experience, reflect

upon that conflict, not least through time, ours and the characters’

(broadly speaking, as human, myth, and hero, though never in linear

fashion, and just as much musically - lyrically and formally - as verbally

and scenically). In a sense, this is true of all opera; ‘all opera is

Orpheus’. But it is perhaps more so here, more overtly so, more

strenuously. Martyn Brabbins and James Henshaw, assisted by Adam Hickox,

did a superlative job of enabling the excellent orchestra, chorus, and cast

to express what they could of this, Peter Hoare a fascinatingly flawed,

multifariously tragic Orpheus the Man, Marta Fontanals-Simmons an alluring,

inscrutable, even alluringly inscrutable Eurydice the Woman, ably supported

by penetrating, intelligently contrasted performances from Daniel Norman

and Claire-Barnett Jones as their mythical counterparts. James Cleverton as

Aristaeus and Claron McFadden as the extraordinary Oracle of the Dead also

stood out dramatically, but there was nothing approaching a weak link to

the cast. Barry Anderson’s electronic realisation, with sound design by Ian

Dearden, proved as liminally dramatic in its way as Stockhausen, as

pregnant with dramatic purpose as an ‘interlude’ in Wagner.

Claire Barnett-Jones. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Claire Barnett-Jones. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

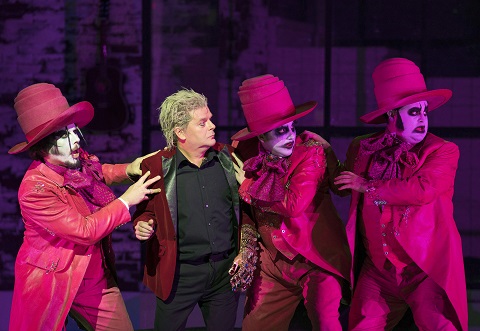

If only Daniel Kramer’s bizarre, ultimately vacuous production had been

remotely equal to its task. Where the work speaks of and with starkness and

complexity, Kramer seemingly mistook the latter for a gaudy variety show,

validated by inclusion of more and more unconnected - with each other, let

alone with the work - acts. This was not the idea of the circus, nor indeed

the idea of anything else; it was a hideous and, doubtless, highly

expensive mess. Occasionally, the possibility of recollection, of memory,

even of dream sequence, asserted itself, more by default than anything

else. For the most part, we suffered an absurd - never, alas, absurdist -

display of exaggerated, ‘saucy’, latex-clad nurses and medical equipment;

of supposedly shocking, yet actually deeply tedious, sexual acts; of people

- often entirely unclear who they were, and to what end - emerging and

sinking into bathtubs; of highly skilled acrobats (for the opera’s mime

action) removing and replacing their clothes, before resuming their

distracting activity; of general hyperactivity that not once seemed to

enquire what it, let alone of anything else, might be for, let alone of

whether its seemingly hapless orientalism might prove a tad problematical

to some. It was unclear that the ‘concept’, if one may call it that, was

anything more than an ageing rock musician - we see the platinum discs on

the wall - Orpheus, holed up in his extravagantly equipped hotel room,

having a bad trip. And even that was perhaps to dignify it.

Was this, perhaps, opera for a world with its eyes - and possibly ears - on

several screens at once, craving instant diversion rather than

satisfaction? Was there even something of the postdramatic to it? I can see

that the argument might be made, but frankly, in this particular case, I

think not; or if it is, then there really ought to be more to it than this.

Constant changing of the emperor’s still newer, still more sparkly, clothes

- ‘by artist, campaigner and designer Daniel Lismore, described by Vogue as “England’s most outrageous dresser”’ - was not enough,

never nearly enough. Nor was there any sign of irony, of critique, of

anything more than camp excess really - which is not to deny the excellent

artistry of those on stage, doing what they could. Carry on Birtwistle, then? It just about qualifies as a point of

view, I suppose; or, better, as the slender basis for one. I cannot help

but think that it would have been better left on the shelf, along with the

rest of this wasteful production: a non-ironic cross between Robert Lepage

and Liberace.

Matthew Smith, Alfa Marks. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Matthew Smith, Alfa Marks. Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

The absurdity might have worked; all manner of things might have worked;

however, in the absence of a connecting pair of ears, let alone anything

between them, this was doomed to remain an endless parade -

in a decidedly non-Birtwistle sense - of effortful vulgarity on- and

offstage, as idiotic as it was wasteful. Wherever one looked, one was

assailed with advertisements for a crystal company to which I shall refrain

from granting further publicity. Nothing could have lain further from the

essence of Birtwistle’s score, nor indeed from Peter Zinovieff’s libretto.

Yet such contradiction was not fruitful; nor even, so it seemed,

intentional. If anything, it simply suggested a director out of his depth -

and not even in the opera’s shallows. The true tragedy, of course, lies in

the damage this may do to prospects for a third production, even for a

further concert performance. Not for the first time, alas, ENO has snatched

defeat from the jaws of victory.

Mark Berry

Harrison Birtwistle:

The Mask of Orpheus

Orpheus the Man - Peter Hoare; Orpheus the Myth, Hades - Daniel Norman;

Orpheus the Hero - Matthew Smith; Eurydice the Woman - Marta

Fontanals-Simmons; Eurydice the Myth, Persephone - Claire Barnett-Jones;

Eurydice the Hero - Alfa Marks; Aristaeus the Man - James Cleverton;

Aristaeus the Myth, Charon - Simon Bailey; Aristaeus the Hero - Leo Hedman;

The Oracle of the Dead, Hecate - Claron McFadden; The Caller - Robert

Hayward; First Priest, Judge of the Dead - William Morgan; Second Priest,

Judge of the Dead - David Ireland; Third Priest, Judge of the Dead - Simon

Wilding; First Woman, Fury 1 - Charlotte Straw; Second Woman, Fury 2 -

Katie Coventry; Third Woman, Fury 3 - Katie Stevenson; Dancers - Joan

Aguila-Cuevas, Sam Ford, Ripp Greatbatch, Stefano de Luca. Director -

Daniel Kramer; Set designs - Lizzie Clachan; Costumes - Daniel Lismore;

Lighting, Video - Peter Mumford; Choreography - Barnaby Booth; Sound design

- Ian Dearden. Chorus of the English National Opera (chorus masters - James

Henshaw, Mark Biggins), Orchestra of the English National Opera/Martyn

Brabbins and James Henshaw (conductors).

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Friday 18th October

2019.