He was also - according to studies such as Peter Ackroyd's 2014 biography

Charlie Chaplin: A Brief Life

- a megalomaniac who treated his wives (invariably much younger) and

children, callously and carelessly. A sexual predator, Chaplin reportedly

estimated that he had slept with 2000 women. In The Charles Chaplin Archives (2015), film historian Paul Duncan

details the scandals - and scandalous efforts to avoid them - paternity

suits and divorce proceedings which led, in 1945, Senator William Langer to

put forward a bill calling for ‘the Attorney General to investigate and

determine whether the “alien” Chaplin should be deported because of “his

unsavory record of law breaking, of rape, or the debauching of American

girls 16 and 17 years of age”’.

So, one asks oneself, why did German director Christiane Lutz (making her

Glyndebourne and UK debut) think that Chaplin, whom she describes as “an

iconic comedian” with “charisma”, has anything in common with Verdi’s cruel

but vulnerable hunch-backed jester, Rigoletto, whose principal aim in life

is to protect his daughter, Gilda, from the corruption of contemporary

society to which he, as he is self-laceratingly aware, contributes?

Lutz takes the 1930s Hollywood studio system as her setting and starting

point. And, this doesn’t seem unreasonable. After all, the casting-couch

sexual predator was no less common then than during our #MeToo age, and the Duke as Hollywood mogul wouldn’t be a far-fetched

notion - just as the Duke as US President, seen last week in

Welsh National Opera’s revival

of John Macdonald’s 2002 Rigoletto is a credible notion. Indeed,

Richard Carr, Lecturer in History and Politics at Anglia Ruskin University

and author of

Charlie Chaplin: A Political Biography from Victorian Britain to Modern

America

(2017),

has noted that

in February 2012, when co-hosting a dinner to honour Chaplin’s services to

the movie industry, Harvey Weinstein remarked that he regarded Chaplin to

be “one of my idols, certainly”. ‘At the time, this appeared to be a fairly

run of the mill commemoration in Tinseltown, but, in the light of recent

revelations about Weinstein, we may now have to view it in a rather

different light,’ writes Carr.

However, there’s a chasm between Verdi’s taunting and tormented jester and

Chaplin, who is often presented as an arrogant genius who manipulated those

around him with no remorse. I seem to have spent much of the past week

reflecting on the relationship between the composer’s score and the

director’s creative response to it, in the theatre and in different

receptive contexts, but while the two WNO productions that I saw in

Birmingham, and the previous evening’s winning

revival of Robert Carsen’s 2011 production of Handel’s Rinaldo

gave much pleasure, even as they raised questions, after sitting through

Lutz’s overloaded, often messy and illogical, and sometimes absurd

production, I found myself siding with pianist Sir András Schiff who, in

2014, in

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

, despaired: ‘What is it with directors? Why is it that most directors find

it so hard to fade into the background and stand in the shadow of the work?

Where did they acquire this addiction for self-expression, pomposity and

disrespect? Why there no humility or modesty? Why this panic fear of

boredom?’

Things didn’t get off to too bad a start, though. A Chaplin-esque

silhouette, visible through a white screen, indulged in some idiomatic

gestural vocabulary, before an old man (actor Jofre Caraben van der Meer)

in modern dress walked into a circle of light. As the Prelude began its

dark dramatic signposting, so the figure stripped off jacket, jumper and

trousers and spun around on the floor on his belly, in underpants and vest,

obsessively writing the single word “forward”, over and over, as it was

simultaneously etched, blotched and obliterated before our eyes on the

screen projection. A short grainy clip of a retired actor, looking back

with nostalgia and bitterness followed. These were, apparently, two of the

three Rigolettos which Lutz leads us to expect: the young man, the older

man fighting against his fate, and “an old man regretting that he can’t

change the past”: “In a movie you can always cut and re-shoot, but in life

of course that’s not possible.”

Oleg Budaratskiy (Sparafucile) and Nikoloz Lagvilava (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Oleg Budaratskiy (Sparafucile) and Nikoloz Lagvilava (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Thus, Lutz has laid the prefatory groundwork, and Act 1 opens in the

spacious brick ‘warehouse’ designed by Christian Tabakoff, a studio-set in

Hollywood’s Golden Age replete with cine-cameras, film techies, extras,

PAs, costume racks and scissor-action bamboos chairs emblazoned with the

names of the significant players: ‘Duca’, ‘Rigoletto’, ‘Monterone’. An

actress, posing against a monochrome backdrop, is harried away by the

director-cum-Duke. Rigoletto, a comic lead, waddles about à la

Oliver Hardy and indulges in some business with a Chaplin-style walking

cane. But, the mood is mild and there’s none of the decadence and

viciousness, jealousy and conflict, that one might expect in Verdi’s

opening scene. The debauchery is going on behind-the-scenes, it appears,

for it’s not long before Monterone - Aubrey Allicock in resounding voice,

wearing a plum-coloured suit to match his face purple with anger - appears,

alongside his daughter (the afore-mentioned actress), who is carrying her

new-born babe.

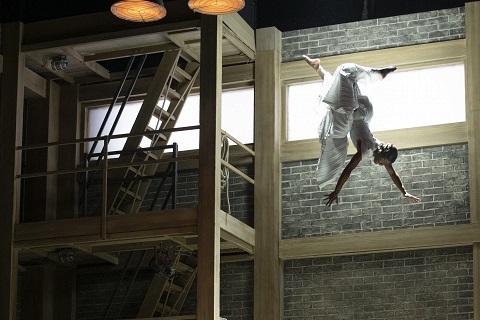

As Monterone denounces the depraved Duke/director, his daughter (aerialist

Farrell Cox) flees up a fly-tower, subsequently to fall in a slow-motion

suicide, rolling head-over-heels, her white skirts billowing like an

angel’s wings. The shock - or Monterone’s subsequent curse - is clearly a

game-changer for Rigoletto: the surtitles tell us that it’s ‘17 years

later’, and the babe-in-arms abandoned on the studio floor is now a young

woman who is under the impression that Rigoletto is her father. Some

unpleasant incestuous relations seem inevitable.

Matteo Lippi (Duke), Vuvu Mpofu (Gilda) and Natalia Brzezińska (Giovanna). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Matteo Lippi (Duke), Vuvu Mpofu (Gilda) and Natalia Brzezińska (Giovanna). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Rigoletto is clearly not a jobbing actor living in a hovel, so we don’t

visit his home. Sparafucile emerges - literally, his suit is half-brick,

half-black - from the walls of the cavernous empty studio; his murderous

suggestions - subtly delivered by Oleg Budaratskiy, whose villainy vocal

and otherwise are of the swift, understated kind - are overheard by the old

man whom we saw in the opera’s opening moments (at least now clothed). And,

it’s to the studio that Gilda rolls up, driven by a chauffeur in a smart

car, with chaperone Giovanna (a rich-toned Natalia Brzezińska, a GTO Chorus

member) in tow. As Gilda questions Rigoletto about her mother, we see the

Duke bribe the chauffeur and don his livery.

At this point, I began to lose sympathy with Lutz’s concept and execution.

Matteo Lippi’s Duke is confident and controlled, vocally and dramatically,

but there is no chink of ambiguity that might intimate genuine feelings for

Gilda - and, in any case, she’s his daughter! Gilda is initially alarmed by

his advances, though she submits, inevitably, to his power and privilege.

In the following scene we see a smirking Duke complete his deal with the

chauffeur, handing over the readies and returning the latter’s uniform in a

corner-seat of Sparafucile’s bar - more Victorian boozer than Hollywood

watering-hole. ‘Parmi veder le lagrime’ the Duke may sing, from the comfort

of his director’s office, but these are crocodile tears. The falsities of

‘La donna è mobile’ - here, bright, agile and virile - represent his

‘sincerity’.

Matteo Lippi (Duke) and Vuvu Mpofu (Gilda). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Matteo Lippi (Duke) and Vuvu Mpofu (Gilda). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The abduction is similarly unconvincing. For some reason, Gilda runs into

the ladies’ lavatories, narrowly avoiding meeting her own ‘father’ on the

hostelry doorstep. The assembled film crew talk of running off with

Countess Ceprano but there’s no clear sense of ill-will towards Rigoletto -

or ‘his mistress’, as in Piave’s libretto. Some Laurel & Hardy-style

japes with a ladder ensue, distracting Rigoletto, and Gilda is abducted -

all without a jot a theatrical tension.

Nikoloz Lagvilava (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Nikoloz Lagvilava (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

It doesn’t get much better when Monterone re-appears, to be ‘condemned’ -

in what court, for what ‘crime’? - accompanied by the ghost of his ‘fallen

angel’, as our aged haunter strokes the floor onto which she fell

(seventeen years ago). Fortunately, there’s no directorial concept on earth

that can destroy the expressive power of Verdi’s Act 3 Quartet. And, though

encumbered with a frightful maid’s costume and soapy mop, Madeleine Shaw’s

Maddalena is striking of voice. As the tragedy plays out, our haunter -

perched on a bar stool - is joined by a grey-haired Duke: it’s all rather

Dickensian, as Time Future visits a Time Present afflicted by the deeds of

Time Past. Without revealing Lutz’s concept-closer, let’s just say that the

time-travelling visitants have a role in the denouement.

Matteo Lippi (Duke) and Madeleine Shaw (Maddalena). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Matteo Lippi (Duke) and Madeleine Shaw (Maddalena). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The central duo - who is this case are not father and daughter,

thereby sending the whole action spinning into a psychological no-man’s

land - do their best, and often that is very good. Vuvu Mpofu is no

ingénue, at least vocally - her soprano burns with passionate feeling, even

if here it is directed at some pretty dodgy targets - and she gives a very

credible dramatic reading in the lamentable circumstances. Nikoloz

Lagvilava makes up for some lapses in accuracy and intonation with a vivid

commitment and a strong, burnished sound that rings with as much genuine

anguish as is possible within this dramatic concept. If at times this

Rigoletto seems somewhat detached, then perhaps that’s because this Rigoletto is not the eponymous jester’s tragedy, but the Duke’s -

and the latter doesn’t seem to care.

Thomas Blunt conducted a careful, often surprisingly understated - but no

less effective for that - reading of the score; the GTO textures were clear

and the colours well-defined. Thanks to some fine singing and playing - and

because The Marlowe Theatre, refurbished and reopened in 2011, is such a

fine venue in which to experience opera - this wasn’t an ‘unenjoyable’

evening, but it was a frustrating one. Verdi and Piave created a terrific

tragic tale; the director’s duty is surely to tell it.

Claire Seymour

Rigoletto - Nikoloz Lagvilava, Gilda - Vuvu Mpofu, Duke of Mantua - Matteo

Lippi, Sparafucile - Oleg Budaratskiy, Maddalena - Madeleine Shaw, Count

Ceprano - Adam Marsden, Matteo Borsa - John Findon, Monterone - Aubrey

Allicock, Marullo - Benson Wilson, Countess Ceprano - Jane Moffat, Giovanna

- Natalia Brzezinska, Court Usher - John Mackenzie-Lavansch, Page - Roisín

Walsh, Actor - Jofre Caraben van der Meer, Aerialist - Farrell Cox;

Director - Christiane Lutz, Conductor - Thomas Blunt, Set Designer -

Christian Tabakoff, Costume Designer - Natascha Maraval, Movement Director

- Volker Michl, Lighting Designer - Benedikt Zehm, Projection Designer -

Anton Trauner, Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus (Chorus

Director, Aidan Oliver).

The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury; Saturday 9th November 2019.