08 Dec 2019

Death in Venice at Deutsche Oper Berlin

This death in Venice is not the end, but the beginning.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

This death in Venice is not the end, but the beginning.

In the opening scene of Graham Vick’s 2017 production of Britten’s Death in Venice for Deutsche Oper, Gustav von Aschenbach finds himself at his own funeral.

An oversize black and gilt funerary frame projects a monochrome photograph of Thomas Mann, whose visage gazes out across a chorus of mourners, their sombre black tempered only by a round wreath of white lilies. This wreath will transform itself into Tadzio’s laurel crown, when he is victorious in the Games of Apollo; then, a gaudy necklace linking the duetting Players - “O mio carino, how I need you near me”; and, subsequently, the barber’s mirror, dexterously angled for Aschenbach to admire his youthful new coiffure. When the increasingly deluded - in this production almost deranged - Aschenbach thrusts his head through the scented circle, it seems to become a noose, foreshadowing his demise.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Much within Stuart Nunn’s single set - a lime-green box, with entrance-exit doors left and right, and lit with lurid tints of yellow and purple by Wolfgang Göbbel - is similarly protean. Black chairs serve as gondolas and children’s playthings, just as Britten’s Elderly Fop reappears as the Gondolier, who becomes the Hotel Manager, who shape-shifts into the Leader of the Players. The seventeen scenes of the opera ebb and flow like the tide on the Lido beach. Yet, there is scant visible representation of the waters on which the city is built: the water which is the source of both the city’s beauty and its decay. Instead, an outsized cluster of violet-hued tulips, their petal-edges curling and blackening, lie stricken. They later serve as the sickness-laden strand of the Lido; their canker is the city’s corrupting cholera.

As the aging, angst-ridden Aschenbach, Ian Bostridge might have wandered in from a Schubert lied, an impression deepened by the presence of the on-stage piano: a wanderer, an outcast, this Aschenbach was a liminal figure, singing from elsewhere, the ‘other side’, trapped within the story - dream or actuality, who knows? - of his own death. And, with characteristic and potent performative immersion, Bostridge coloured the text, ‘bent’ the melodic lines, surged, sometimes snarled, through the increasingly emotive utterances of delusion, desolation and defeat. He swayed and staggered, leaned back and curved forward; he reclined against and then climbed onto the piano. Yet, while at times almost overcome by his awareness of loss of dignity and unalleviated despair, in the recitatives Bostridge’s Aschenbach stood erect and sang with vocal pristineness and clarity of thought - even if it was the lucidity of a deluded mind in self-denial. At such times, Bostridge moved to the fore of the stage and sang directly to us. His stare was unwavering, unnerving, as if Aschenbach was facing his own image in a mirror which would brook no dishonesty.

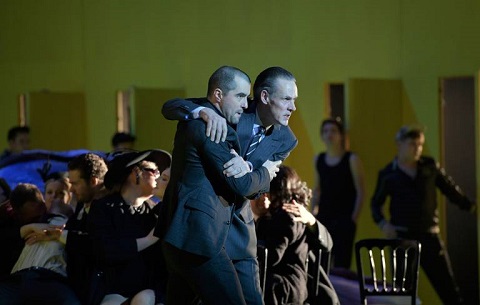

Seth Carico (as the Traveller) and Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Seth Carico (as the Traveller) and Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

There is little communication, in either Mann’s novella or Myfanwy Piper’s libretto, between Aschenbach and the other characters, but here the distancing of the protagonist seemed even more pained and severe than is customary. Frequently his fellow tourists would turn their backs on the writer and gaze seawards; when the barber came to refresh his client’s ‘youthfulness’, Aschenbach stood behind, regarding the cosmetic mime with hubristic pleasure.

Bostridge made Aschenbach’s mental and moral disintegration evident from the very start. His proud pronouncement, “I, Aschenbach, famous as a master-writer, successful honoured, self-discipline”, was less an assertive self-definition, and more an angry riposte. He clutched the strange Traveller when he sang of the South, and of the “terror” in the bamboo grove - “a sudden predatory gleam, the crouching tiger’s eyes"; he allowed the Gondolier to stroke his hair and shoulders, as his fellow travellers’ gentle sway intimated both the rocking waves and the gesture of caress.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Taking off his shoes and socks, rolling up his elegant trousers, Aschenbach strolls along the poisonous promenade; when the strawberry-seller appears atop the tulip mound to extol her wares, Aschenbach gorges on the red fruit. The children’s games turn spiteful: they steal the writer’s shoes and toss them back and forth like a beach ball. The young playmates’ movements blend stylisation and naturalism: Rauand Taleb’s Tadzio is lithe and strong, his lofted body thrown and caught by his friends, his victorious form hoisted heavenward. Having calmed himself, accepting that his vocation demands that he must “dedicate [his] days to the sun, and Apollo himself”, Aschenbach settles down to observe the physical embodiment of his revered Hellenic beauty, only to be confronted with the children’s taunting game of ‘pyramid building’, their splayed limbs dangling erotically across the tulips, deepening the petals’ purple bruises.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Apollo - a potently penetrating Tai Oney - may shine a light, from a cameo-light camera, to illuminate Aschenbach’s way but it is too late: he is lost … in a moral maze whose minotaur is Eros. It is not clear in this production what is remembered or what is real. Tadzio (Rauand Taleb) does not seem to see Aschenbach, but the latter is provoked by an imagined or intimated smile. After the Players’ grotesqueries, Tadzio seats himself under Aschenbach’s desk, and the writer imagines a communion of like minds: “Ah, little Tadziù, we do not laugh like the others. Does your innocence keep you aloof, or do you look to me for guidance?” Bostridge made the end-of-Act 1 declaration, “I love you”, strikingly assertive: there was a sense of release, then a brief hint of brazenness, and then a look of horror: what had been acknowledged could not be unsaid, nor the consequences evaded.

Rauand Taleb (Tadzio) and Tai Oney (Apollo). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Rauand Taleb (Tadzio) and Tai Oney (Apollo). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

When the curtain rises on Act 2, a viciously scrawled “Achtung” shrieks its warning from the rear wall, its dripping ink as viscous as the city’s black waters. Wolfgang Göbbel’s lighting casts a surreal sheen on the Dantesque figures who haunt the hinterland, grimacing and lurching as they fall prey to city’s choleric clutches. And, as Aschenbach obsessively follows Tadzio and his family through the city, both the indignity and recklessness of his pursuit are embodied by the cesspit of writhing bodies - the lapping water - at his feet.

During the Dream sequence, Dionysus (Seth Carico) removes his shirt and squares his shoulders at the besuited Apollo, before a nightmarish dervish ensues, worthy of the Hieronymus Bosch allegories that I had found so disturbing in the Gemäldegalerie earlier that afternoon. And, there is much chest-baring in this production. Tadzio and his young friends posture and pounce with a boisterousness verging on, and spilling over into, aggression, as Tadzio is baited and doused with water. Similarly, on the boat to Venice, Aschenbach’s fellow travellers break out in vulgar songs which here seemed to have a repressed violence in their rhythmic energy, equal to the mutinous dynamism of the shanties in Billy Budd.

Seth Carico (as Elderly Fop). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Seth Carico (as Elderly Fop). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

As the eerie composite figure who haunts Aschenbach, Seth Carico’s voice was as mutable as his costume was candidly uniform: black, with merely the occasional addition of a camp feather boa or hat to distinguish his incarnations. Vocally, Carico was a disturbingly elusive Traveller; then, as the repulsive Elderly Fop, he exhibited a silken baritone which flipped upwards with startling slickness to a falsetto both astonishing and atrocious. After the lively duplicity of the Barber and the firm, forthrightness of the Hotel Manager, Carico’s Leader of the Players was lewd and bellicose - discomfortingly so as he held up a titillated customer’s chin lasciviously, leeringly, before delivering a cruel slap to the proffered cheek. Another pitiful onlooker had his shoes removed and his feet crammed into stilettos - a reminder of the bare-footed Aschenbach’s humiliation, perhaps - and his neck wreathed in the Leader’s glitzy feather boa. As he stumbled drunkenly to the lurching rhythms of the ghastly song, “How ridiculous you are!”, the troupe’s drum-beat “Ha!”s seemed literally to flagellate and shame.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Although Death in Venice is essentially a one-man show, Britten asks for a large cast and here those taking the smaller roles were excellent. Samuel Dale Johnson was particularly impressive as the English Clerk, piling up chairs agitatedly as he revealed, with an anxious tinge and good projection, the malignity which would menace Aschenbach should he stay in Venice. As the provocative Strawberry Seller soprano Alexandra Hutton’s sales pitch had a freshness that her fruit certainly did not share. Andrew Dickinson was accomplished as the Hotel Porter.

Conductor Markus Stenz drew some surprisingly dark colours from the Orchestra of Deutsche Oper. Usually the elements of Britten’s score which strike me most are the flashes of colour and brightness from harp, glockenspiel, vibraphone, bells, xylophone; on this occasion, I was sucked into the oily blackness of bassoon, bass clarinet, low strings, trombones and tuba: just right for Vick’s scheme of things.

The production and performance had many merits, but this was, inevitably, Ian Bostridge’s evening. Having been so moved by Mark Padmore’s performance in David McVicar’s new ROH production , I feel very fortunate to have heard two of the greatest English tenors of recent years perform this role in two very different productions, just a couple of weeks apart.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Ian Bostridge (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Bettina Stöß.

Towards the close, there was an intimation that Aschenbach had found some peace: “Does beauty lead to wisdom, Phaedrus?/ Yes, but through the senses./ Can poets take this way then/ For senses lead to passion Phaedrus?/ Passion leads to knowledge/ Knowledge to forgiveness/ To compassion with the abyss.” Bostridge delivered such contemplations with the sweet softness of the gentlest lied: clear, tender, true. But, this moment of purity was followed by a terrible irony and bitterness. The latent violence finally broke through the barriers of social restraint. The flickering rivalry between Tadzio and his friend Jaschiu (Anthony Paul) caught fire, and the ensuing fight left Tadzio lying prone, unmoving, his limp form far from his former Hellenic statuesque-ness. Aschenbach clasped the boy in his arms; when the had departed this life, so the writer made his own last exit.

Some productions subtly intimate that, with his death, Aschenbach has found inner reconciliation and become one with “the sea, immeasurable, unorganised, void” in which he has longed “to find rest in perfection”. Vick’s re-imagining of the close denies the writer, and the audience, any such consolation. I found myself recalling the reflections (in an essay ‘The Romantic Song’) of Roland Barthes: ‘The lied’s space is affective, scarcely socialized: sometimes, perhaps, a few friends - those of the Schubertiades; but its true listening space is, so to speak, the interior of the head, of my head: listening to it, I sing the lied with myself, for myself. […] The lied supposes a rigorous interlocution, but one that is imaginary, imprisoned in my deepest intimacy.’ This Aschenbach seemed so utterly, terribly alone, inside his own song of death.

Claire Seymour

Britten: Death in Venice

Gustav von Aschenbach - Ian Bostridge, Traveller/Old Gondolier/Hotel Manager/Elderly Fop/Hotel Barber/Leader of the Players/Voice of Dionysus - Seth Carico, Voice of Apollo - Tai Oney, Tadzio - Rauand Taleb, Strawberry Seller - Amanda Hutton, Hotel Porter - Andrew Dickinson, English Clerk/Polish Father, Russian Mother/Lace Seller - Flurina Stuckl, French Girl/Newspaper Seller - Meechot Marrero, Danish Mother/Street Singer - Samantha Britt, English Mother - Joanna Foote, French Mother - Michelle Daly, German Mother - Irene Roberts, Russian Nanny - Anna Buslidze, Polish Mother - Lena Natus, Glassblower - Gideon Poppe, Gondolier/Street Singer - Marwan Shamiyeh, Second American/Gondolier/Hotel Guest - Matthew Peña, Hotel Guests (Helen Huang, Anna Huntley, Karis Tucker, Ya-Chung Huang, Stephen Barchi), First American - Michael Kim, Beggar - Davia Bouley, Lido Boatman/Waiter - Timothy Newton, Steward/German Father, Tourist Guide - Matthew Cossack, Gondolier - Philipp Jekal, Onstage Pianist - Adelle Eslinger, Onstage Musicians - Kelko Kido-Lerc, Sebastian Molsen/Friederike Roth, Jaschiu - Anthony Paul, Tadzio’s sisters - Ebru Dilber/Mimi Nowitzki, Tutor - Anne Römeth, Friends of Tadzio (Maximillian Braun, Joshua Edelsbacher, Alexander Gaida, David Lehmann, Per Kreutzberger, Alexander Shanck), Young Girls - Victoria Kraft/Selina Senti, Venetians (Cristiano Afferri, Marco Ordovas, Danilo Valentini); Director - Graham Vick, Conductor - Markus Stenz, Designer - Stuart Nunn, Lighting Designer - Wolfgang Göbbel, Choreographer - Ron Howell, Choir and Orchestra of Deutsche Oper Berlin.

Deutsche Oper Berlin; Thursday 5th December 2019.