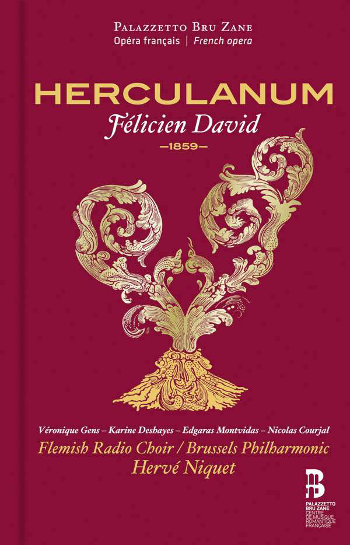

The French

record magazines have been near-unanimous in praising the resulting 2-CD set,

and the work itself. No doubt in part because of this sudden success, Wexford

Festival Opera (in Ireland) has announced that Herculanum will be

one of the three operas in their Fall 2016 season. The other two will be

Vanessa, by Samuel Barber, and Maria de Rudenz, by Giuseppe

Donizetti. Classy companions for a long-obscure composer and work!

Indeed, until now, opera lovers—including singers and musicologists—had

no means of experiencing Félicien David’s only grand opera Herculanum

(1859) except by playing and singing their way through the original

piano-vocal score, which can be found in many large music libraries or

downloaded at www.IMSLP.org. (The full

score is likewise at IMSLP.) A single aria, Lilia’s “Je crois au Dieu,”

continued to be published and performed into the early twentieth century,

though deprived of its highly dramatic choral component. It, too, then vanished

like the rest. With the present release, we now have ready access to the full

work (well, not quite all of it), in a performance that ranges from highly

proficient to masterful.

Félicien David (1810-76) is not even a name to most musicians and music

lovers. His only frequently performed number is “Charmant oiseau,” from the

first of his four French comic operas, La perle du Brésil. That aria, with

obbligato flute, has been recorded by numerous coloratura sopranos across the

decades, from Amelita Galli-Curci to Sumi Jo. In recent years, though, his

output as a whole has been gaining more attention. The songs

and chamber and solo-piano works were major rediscoveries.

A recording of his second comic opera, Lalla-Roukh—though minus its crucial connecting spoken dialogue—revealed it

to be consistently accomplished, even at times magical. And one work has even

been recorded twice: Le désert, an engaging fifty-minute secular

oratorio (for one or two tenors, chorus, orchestra, and narrator), set in an

unnamed Arab-world desert. As the work unfurls, a caravan moves across

blistering sands, entertains itself while stopped for the evening, hears the

morning call to prayer, and then sets off for another day of grueling travel.

(The second, and more persuasive, recording of Le

désert recently won a Grand Prix du Disque for the “repertoire

rediscovery” of the year.)

The various works just mentioned are, for the most part, gentle and tuneful,

with colorful touches in the orchestra. By contrast, a nineteenth-century

French grand opera, composed for the prestigious Paris Opéra, needed to

traverse a wide range of intense emotions and contrasting moods, corresponding

to the libretto’s hefty conflicts between political powers, social classes,

or religions. Opera lovers have a sense of the “French grand opera”

genre—not least its sometime monumentality—from such works as Meyerbeer’s

Les Huguenots, Halévy’s La Juive, and Verdi’s Don

Carlos. (Also from a German work that draws heavily on devices typical of

the genre: Wagner’s Tannhäuser.)

In 1859, many musicians and critics in Paris wondered whether the composer

of the ear-tickling “Charmant oiseau” could meet the very different

challenges of grand opera. As it turned out, Herculanum became a

success, holding the Opéra stage 74 times during the next nine years.

Indeed—as we learn from a richly detailed essay by Gunther Braam in the

hardcover book that comes with this recording—Herculanum was, in its

day, performed at the Opéra nearly as often as Gounod’s Faust and

Verdi’s Les vêpres siciliennes and more often than Mozart’s

Don Giovanni. The numerous published reviews—excerpted and evaluated

in the book—praised the singers and the impressive sets and staging.

Contemporary illustrations and affectionate caricatures of scenes from the

opera—likewise reproduced here—give some sense of the visual splendor.

(Full disclosure: I wrote the booklet’s essay on the composer’s life, but I

had nothing to do with the recording.)

The opera takes place in Herculaneum, a city near Pompeii, in the year 79

A.D., just before the famous eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. (In English, the

town’s name contains the second e; in Italian it’s Ercolano.) The central

tension is between a chaste, unmarried young Christian couple, Lilia and

Hélios, and a nefarious sister-brother pair from the Middle East: specifically

the Euphrates valley. Olympia has come to Herculaneum to be named queen of her

native Eastern land by the Romans; Nicanor, Olympia’s brother, has been

raised to the position of a Roman proconsul. Consistent with the prevailing

operatic practice of the day, the two good characters are a soprano and tenor

and the bad ones are a mezzo-soprano (or contralto) and a bass-baritone. Less

typically, the latter two have some attention-getting passages of coloratura.

The only other solo role is that of a Christian holy man, Magnus—another

bass-baritone—who occasionally declares doom for those who practice sinful

ways.

In Act 1, Olympia seduces Hélios by means of a potion, her dazzling beauty,

and the splendors of her pagan court. In Act 2, the devious Nicanor tries to

win the affections of Lilia, but the Christian virgin remains steadfast in her

devotion to Hélios and to the God of Christianity. Frustrated, Nicanor

declares that her god does not exist. A bolt of lightning strikes him dead,

suggesting that his theology is faulty. Satan appears and shows Lilia, in a

magical vision, what her sweetie-pie has been doing at Olympia’s court. Satan

then grabs the corpse’s cloak so that, disguised as a mortal, he can continue

stirring up misery on earth.

Act 3 begins with a great festival in Olympia’s court, at which Hélios

appears; then Lilia, who, dropping to her knees, sings a stirring Credo: the

aforementioned “Je crois au Dieu”; and finally Satan, now disguised as

Nicanor. (Lilia, in horror, recognizes him, but, perhaps out of fear, does not

alert the others.) Hélios is briefly torn, but, during an impressive

act-finale, in which the characters interweave their music and words with much

intensity, he—in order to save Lilia from being put to death by the

pagans—claims again to love Olympia. Act 4 begins with Satan gathering the

city’s slaves and urging them to avenge themselves on their masters. (He

calls them “sons of Spartacus,” alluding to the famous slave revolt.) In

the final scene, during which Vesuvius has already begun to shake the earth,

Lilia and Hélios are briefly reconciled; their extensive duet was much praised

by Berlioz and others. Satan reappears and causes Vesuvius to erupt. As hot

lava buries the pagan city and all its inhabitants, the two Christian

lovers—at least one of whom is still chaste—sing of their redemptive ascent

to heaven.

The opera’s music largely resembles that of French grand operas of the day

(and certain relatively serious opéras-comiques) that are somewhat

better known today, by such composers as Auber, Meyerbeer, and Gounod. Several

of the solo and duet cabalettas are similar in style to ones by Bellini and

Donizetti (e.g., Norma’s “Ah! bello, a me ritorna”), and quite convincing

in context. The orchestra sometimes provides refreshingly quirky effects. For

example, the scene in which Satan urges the (male) slaves to rebel against

their masters may remind listeners at times of certain fantastical moments in

Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, a work that was performed twice in

Paris in 1846 but not again for some thirty years. (The entire ten-minute scene

can be heard on YouTube.) Audiences in David’s day, hearing this same

scene, may have recalled instead something that at the time was much more

familiar: the “Infernal Waltz” scene in Meyerbeer’s Robert le

Diable (“Noirs démons, fantômes”), in which Bertram convokes the

spirits of hell (male chorus) to help him ensure his son’s destruction.

The Christian religious element is well caught by the composer in Lilia’s

“Je crois au Dieu” in the middle of Act 3. The

tune’s solid squareness makes it feel hymn-like and helps us appreciate the

Christian maiden’s bravery and commitment, especially when the chorus of

pagans calls for her death while she continues singing her profession of faith.

The gradual entry of harp and then cornets to the orchestra as the number

advances adds further grandeur and tension . The dramatic effect, in a

live performance, of this faceoff between Christian soloist and pagan chorus

can be sensed in a video

excerpt—recorded in concert—by the same performers who are heard in the

present recording. (That video “trailer” begins with the opening of the

opera’s prelude and concludes with two excerpts from the big Act 4 duet

between Lilia and the now-remorseful Hélios.)

A powerful confrontation of vocal forces likewise occurs in Act 1, when the

pagan couple and their courtiers ridicule Magnus’s call to repent and to

foreswear their evil ways. The pagans’ jaunty music here seems closely

modeled on the main theme of the closing section in Act 1 of Rossini’s Le

Comte Ory. Indeed, numerous passages in the work have an

opéra-comique lightness to them, appropriate to the pagans’

celebrations of pleasure and to their frequent expressions of sarcasm toward

the outnumbered, impoverished Christians.

Only the very ending of the opera disappoints. David was hardly the composer

for convulsive cataclysms. In fairness, though, the closing music was not meant

to stand on its own—as it must in a recording—but to accompany a

spectacular visual effect: Vesuvius erupting and destroying the town and

everyone in it.

Among the many notable passages in the opera, I particularly like four that

occur (or, in two cases, first occur) in Act 1. The romance sung by

Hélios and then Lilia, “Dans une retraite profonde,” is a touching,

sweet-sad description—with an exotically sighing oboe solo in the coda—of

the modest, secluded life, religious commitment, and pure love that the two

innocents share. (In Act 3, this romance will be restated in its

entirety by the English horn while Lilia, in freer phrases over it, attempts to

draw Hélios back from pagan bliss.) Olympia’s drinking song, the centerpiece

of Act 1, uses a vigorous polonaise or bolero rhythm; perhaps this attractive

number served as a model for “Je suis Titania,” a splendid aria—with

similar rhythm—in Ambroise Thomas’s opera Mignon. The orchestral

interlude portraying the effect of the love potion on Hélios is vividly

descriptive, an aspect that Berlioz—not surprisingly, given his compositional

inclination toward the descriptive or programmatic—specifically admired in

his review. Hélios’s ecstatic declaration of love for Olympia, “Je veux

aimer toujours” (“I want to love forever in the air that you breathe, O

goddess of sensuality!”)—sung soon after the weak-willed man drains the

potion-filled goblet—was much praised by Berlioz and other critics as being

“truly inspired” and full of “passion” and “elegiac gracefulness.”

Lilia is not on stage when Hélios sings this hymn in praise of the queen’s

eyes, smiles, and “flower gardens” full of “balmy ecstasy.” The Christian maiden finally

gets to hear, horrified, his traitorous song at the end of Act 2, when Satan,

as noted earlier, uses his supernatural powers to let her see and hear—as if

on a closed-circuit television monitor—Hélios, now decked in royal finery,

sitting at the feet of the pagan queen Olympia, and singing his smitten joy

.

All in all, this 2-CD set allows us to appreciate new aspects of David’s

compositional deftness. For example, when a vocal melody or phrase is restated

but to a different set of words, the composer often subtly adapts it to the new

words, more than was usual in French and Italian operas of the day. This may

make the vocal parts a little trickier to learn. But, in the end, it surely

helps the singer articulate the new words in a natural and expressive manner

and thus also helps the audience hear the words and grasp their point. (See,

for example, Lilia’s reworking of the melodic line of “Dans une retraite

profonde,” which had first been sung by Hélios. Not to speak of the more

extensively altered return of this music in Act 3, involving the aforementioned

English-horn solo; this moment was among the many that Berlioz singled out for

special praise.) More generally, even certain numbers that may sound

conventional at first—the festive choruses, an orchestral march—display

intriguing touches in phrase structure, orchestration, or choral texture.

The five vocal soloists do the score proud, articulating vividly the

old-fashioned but elegantly worded text. (Mary Pardoe’s English rendering in

the accompanying book is admirable: accurate without ever sounding stilted. Her

English version of the synopsis is more helpful on a few plot points than the

version printed in French.) Orchestra and chorus are precise and full-toned.

One minor objection: the English-horn player could have been more eloquent in

his Act 3 solo, and even omits a particularly beautiful ornament written into

the score.

My only overall complaint is that the recording favors the voices too much.

For example, in CD 2, tracks 9 and 11, I had trouble hearing the orchestra’s

changing harmonies until I switched to headphones. Similarly, in Hélios’s

song of ecstasy to Olympia (CD 1, track 21), a listener is not made clearly and

consistently aware of the 12/8 meter. David’s decision here to divide the

beat into triplets, in the orchestral accompaniment, could have been made more

evident to the ear; this would have increased the sense of illicit, throbbing

desire that contributes so much to the dramatic tension in this work.

Herculanum sometimes feels like a close predecessor to Samson et

Dalila, a work that Saint-Saëns was just beginning to compose around this

time and would toil away at for more than a decade.

Edgaras Montvidas is

a Lithuanian tenor who performs in major opera houses and concert halls in

Europe and America: for example, Lensky at Glyndebourne and the Bavarian State

Opera, and Don Ottavio in Santa Fe. As Hélios, he maintains a firm, sweet

tone, even when expressing (very well) such extreme emotions as ecstasy or

remorse. His French is remarkably good, except on the nasal-i (e.g.,

jardin, ainsi). Véronique Gens is utterly magnificent

as Lilia, maintaining a full, rounded sound even while conveying much dramatic

specificity. Karine

Deshayes, as Olympia, is at once commanding and subtle, quite an

achievement. Occasionally she seems too far from the microphone to make full

effect (as in Olympia’s coloratura-rich commentaries over the second

statement of Hélios’s “Je veux aimer toujours”). Though these three

masterful singers have never performed the work on stage, they bring remarkable

alertness and seeming spontaneity to their solos and to ensemble scenes.

Nicolas Courjal ,

the singer of the roles of Nicanor and Satan, engages in frequent, incisive

word-pointing, which would be welcome in a live performance. But, for a recording

that one may want to listen to numerous times, I find his vocal quality

grating: the vibrato on long notes is slowish (though fortunately not wide),

the coloratura is labored, and short notes are not always perfectly pitched. As

a result, his Nicanor is less than seductive in the fascinating Act 2 duet with

Lilia. Imagine a young Samuel Ramey sinking his teeth into this double-role!

Still, Courjal never forces or barks.

(An interesting complication: At the premiere, the roles of Nicanor—plus

Satan in the guise of Nicanor—and Satan—as himself—were split between two

different bass-baritones, perhaps mainly as a way of managing to have Satan

appear while Nicanor’s lightning-struck body is still on stage. But having

one singer take both roles works just fine on a recording, perhaps even better,

since the characters are never present—or, rather, present and alive—at the

same time.)

At the end of Satan’s scene with the slaves, Courjal manages the tricky

scalar runs by gargling the notes rather than connecting them smoothly as the

score plainly implies (“Ah . . .”); this can be heard in the ten-minute-long YouTube

excerpt mentioned above, beginning just after the eight-minute mark. I

suspect that here the performer is turning a limitation into an asset: the odd

vocal production intensifies the weirdness of the moment and impresses the runs

on our memory, so that, when the string instruments restate them in the

scene’s creepy coda, we instantly recall Satan and his nastiness.

As for Julien

Véronèse, who sings the smaller role of Magnus, he is a youngish bass

(born 1982), frequently appearing in roles such as Sharpless, Colline, and Dr.

Grenvil at secondary opera houses in France. He is capable here but, like

Courjal, not ideally steady. More basically, he lacks the deep, rolling

resonance that would help convey the moral authority of this divinely inspired

prophet. One’s thoughts naturally turn to the sort of singer who could have

made more of this character’s dramatic recitatives: say, José Van

Dam or René Pape.

The recording omits, in Act 3, one major vocal number for Olympia (a Hymn to

Venus: “Viens, ô blonde déesse”)—much praised by Berlioz and

others—and the entire divertissement that follows it: an

extended ballet, a choral hymn to Bacchus, and a chorus-assisted Bacchanale.

Since CD 2 is only 49 minutes long, it could easily have included all the

omitted numbers. (The aria was omitted because the mezzo-soprano was indisposed

in the final days of the recording sessions.) This drastic cut, though, should

in no way dissuade anyone from purchasing the recording, which—many opera

lovers who hear it will agree—is one of the most important classical releases

of 2015.

Herculanum is the tenth item in the ongoing “Opéra français”

series produced by the renowned Centre de musique romantique française,

located at the Palazetto Bru Zane (Venice, Italy). A convenient listing of the

whole series, as well as of two parallel series—Prix de Rome cantatas and

composer-portraits—is located at the website of the Centre. A lengthy article about the

French-opera series—including an interview with the Centre’s

enterprising and astute director Alexandre Dratwicki—appeared in the October

2015 issue of Gramophone.

As for the

upcoming performances at Wexford, I trust that the missing sections of Act

3 will be reinstated, and hope that a video recording will be released

commercially or made available online.

Ralph P. Locke

Musicologist Ralph P. Locke (Eastman School of Music) comments

further on music by Félicien David in Jonathan

Bellman, ed., The Exotic in Western Music (Northeastern

University Press, paperback). The present review appears here with the kind

permission of American Record

Guide, where it first appeared (in somewhat briefer form).